Occitane Lacurie and Barnabé Sauvage

Image as Stock. On Capital Image, Centre Pompidou, 2023-2024.

Interview with curator Estelle Blaschke

Abstract

Capital Image is an exhibition conceived by the researcher Estelle Blaschke and the photographer Armin Linke, which proposes to think of photography as an information technology capable of measuring and quantifying the world for speculative purposes. Put into flux by their images, things can then circulate along the highways of information and commerce. Capital Image proposes to make an archaeology of this government by vision, mixing documents and works of various kinds in a curatorial proposal and a research project that we wanted to discuss with Estelle Blaschke./p>

Keywords

operative images, stock images, information technology, media archaeology, photography

Electronic reference to cite this article

Occitane Lacurie and Barnabé Sauvage, « Image as stock. Interview with Estelle Blaschke (English version) », Images secondes [Online], 04 | 2024. URL : http://imagessecondes.fr/index.php/2024/12/image-as-stock-interview-with-estelle-blaschke-english-version/

Image 1. Exhibition Capital Image (Centre Pompidou, 2023-2024).

From Banks to Currency

In 2011, you finished a PhD in history of photography about image banks, later published under the title Banking on Images: The Bettman Archive and Corbis (Spector Books, 2016). In your dissertation, you wanted to show the historical formation of visual archive funds and interpreted them as a form of accumulation—and further commodification—of images. After this first research, was it only natural for you to continue your work toward photography as a currency and image as capital?

My previous work on image databases considered the archive as a foundation for the commodification of images in the 20th century. Working on the idea of accumulation of images wasn’t something obvious at the beginning of the 2000. But there was a major change between this work finished in 2011 and the shift that appears a few years later, when the smartphone allows for the possibility of creating masses of images, and when technology gave the ability to compute on these newly formed masses of data. The topicality of image banks and the question of the archives become ever more important when we consider contemporary digital images practices, because we are talking about big data, which you could mine, analyze, remodel, etc. Even if I didn’t consider that at the time, it has been very interesting to continue to work on photography, not as artistic form, but rather as a potential of masses of images–to work on the logic of masses and archive, and the relationship between images and metadata, categories, and the politics of metadata. These interests were contained in my first project, in a way, but not as much as it is tackled by this exhibition today.

This project started 5 years ago with a series of conference photograph Armin Linke and I gave at Centre Pompidou, with Trevor Paglen and Hito Steyerl, to reflect on the futures of photography. During my lecture, I sketched out my ideas on the concept of photography as information technology, a reframing of the history of photography not so much focusing on aesthetics but also functional aspects. Florian Ebner asked me to continue this research program and to develop this in an exhibition. This was the starting point for a series of field work and laboratory visits, where Armin and I went to the places where digital technology was designed and apply, to understand how they work with that operational way of images. This project was difficult because it is in a way a sort of black box that demands analysis. I’m a photo historian, but I also try to understand how we can understand photographic history through the lens of the contemporary. Armin Linke is an artist working as a visual researcher: his research device is the camera, and interviews made to understand how the images practices are explained by practicians themselves.

Image 2. Exhibition Capital Image (Centre Pompidou, 2023-2024).

Just before this project, between 2015 and 2020, you worked on the historical uses and value of microfilms. Your work questioned photography not only as a visual form but also as an “enriched” form through captioning–and nowadays by metadata. In the third issue of the photography journal Transbordeur, which you directed, you also wrote the article “From Microform to Drawing Robots. The role of Data in the Photographic Image”, in which you claimed that “methods that aim to make images more informative belong to a capitalist logic of optimization of images toward utilitarian ends.” If, traditionally, the value of image was tied to its material value or the value of the represented object, and then, in Modern times, to its artistic value, would you say that value is now bounded to its potential exploitation as a text or an asset in a database?

There is a connection between these phases, but there is also a real paradigm shift in the contemporary era. I would like to start with the idea that we had, in the exhibition, to show a lot of quotes coming from the very beginning of the history of photography. We must keep in mind that photography as a device of creating images, generating images technically, comes at a time of development of industrialization–which is also the development of capitalist society forms. In that article, I posit that we really must look at the direct link between the history of photography and industrialization. Photography is indeed a very efficient way of visual documentation, and microform only increased that operationality, but it we can also consider earlier forms of documentation, such as Aimé Girard’s Research on the cultivation of the industrial potato (1889). Photography represents a depth of information gathered in a visual appearance. You can describe it with text, but it’s much easier to do in a form of heliogravure with a lot of details included–layers of information that are part of a research and that have a lot of values, as it is the case nowadays for researchers and for companies that try to optimize it… That is why we wanted to highlight the role of images in that process of gaining values.

For instance, we went to the Netherlands, to visit greenhouses owned by companies such as Ter Laak Orchids or Priva that are pioneers in data-driven industrial productions. To investigate on their process of production of orchids or tomatoes, we visited huge compounds of several millions of plants. In this context, photographs aren’t only the documentation of production, but also a condition sine qua non of production. Every single orchid is going through the process of a photo studio, a container box where the plant comes and is photographed several times to make a 3D model and identify the bulbs, the growth, etc. The data gathered is then used to develop software to help the regulation of irrigation, temperature in the green houses, light levels, etc. It has a lot of implications for the environment.

Images 3 to 6. Armin Linke, Priva, tomato greenhouse, Priva Campus, De Lier, Netherlands, 2021 and Armin Linke, Ter Laak orchids, orchid production line, Wateringen, Netherlands, 2021.

The bigger picture of this research is, on the one hand, the study of optimization as a part of capitalist thinking, and on the other, the study of visual technologies that are increasingly shaping our environment. Something built in the immaterial realm (computing, software, analyses, etc.) is determining how the material (architecture of optimal green houses, rendering of 3D models) is shaped. Here we can observe the paradigm shift: photography is much more than passive documentation, but an action toward the transformation of the world and our perception.

In that context, the act of equipping a robot with the sense of vision is very meaningful. To the point where there is not much real people in these images. These laboratories or factories are places where the human is absent–in the European organization for nuclear research (CERN), or in the greenhouses. It’s empty: only machines and programs; the human comes only when there is a problem. This is quite a reversal: it’s not the machine that assists the human, but the human that assists the machine. This new place for the human and its agency, this new distribution of what we can understand or maybe even change, is deeply linked to the new developments of capitalism. These is what we called in the exhibition digital capitalism or extractivism, which is a lot shadier, and opaque than the tradition form we were used to. We now have very little tools to understand what the training sense are, and what is really going on there. And this is why we are investigating.

For instance, we interviewed some collaborators of the Big Five, such as Google, to understand how they are using these new archival possibilities. They told us that everything changed with the mass of data. They consider not only the images but also the visual layout, which is very rich. This proved to be interesting for my newest research on the recent developments of metadata protocols. In the camera, you have an array of data collected, it was not the case 10 years ago: now every image is situated in space, time, technical aspects such as the ratio, colors, etc. And you can also add more recent developments, such as intellectual property, included right through blockchain. Everything has become the basis of mining information and training of algorithms. And that’s a very useful source of “free” information for companies, such as the pictures circulating via WhatsApp and then connected to Meta…

Labor, Computational Capitalism and Advertising

The “Mining” section of the exhibition proposes to analyze data mining (image identification, tagging, database organization, etc.) as raw material extractivism. And several works in the exhibition expose how databases are filled by the underpaid work of those Antonio Casilli calls the “click workers”. A lot of this shadow work is, however, crucially important for the training of so-called “artificial intelligence”, which in fact use all this primitive accumulation of information as a step for development. How could we describe this new form of exploitation in what you called computational capitalism?

To better understand this topic, we could have a look at that piece called Meta Office: Behind the Screens of Amazon Mechanical Turks (2021), the only external piece of the exhibition. It’s from a group composed of former students from the Technical University of Delft under the supervision of Georg Vrachliotis. They wanted to work on the future of the office, and how its shape would follow the dislocated logic of the gig economy. They gathered over 500 images via an assignment given to Amazon Mechanical Turk workers. They asked them to take a picture of their environment and place of work, and to tag that image. They would be paid and be asked for their consent. The work is the combination of all these different places: you can see how they look visually, but you also have the metadata connected to the place and the timing of the photo, and to the amount of money they get paid. This brilliant piece aims at unraveling the whole logic of this opaque world.

Image 7. Meta Office: Behind the Screens of Amazon Mechanical Turks (2021).

These metrics (income per hour, amount of square meter of the office, etc.) appear to be quite a subversion of the logic of metadata you exposed us previously. This over-contextualization tends to show that work isn’t done by someone immaterial but rather by human beings with needs and specific position in the labor chain.

It’s indeed very important because this idea of dematerialization has always been a catalyst for the representation of flow of information, data gathered for no money, for resources not physical. There is a shift of materiality at stake here: labor is done in different places, outsourced not only to a Third World country, but also dislocated from the company to opaque fields–but it’s still there. And the same goes with natural resources used to maintain these spaces (servers, etc.): there’s a materiality which I call second degree materiality, behind the obvious palpable realm.

Do you think that kind of metadata should be attached to every image so we can have a grasp of which kind of materiality we’re dealing with whenever we see an image? Could it make things less opaque?

It would be a way to bring back the human. This idea would shift to the political aspect of data, which is usually kept out. This work is intelligent because it works on so many levels: data, vision, the human space in which everyone lives. We can also read this piece with this quote from Walter Benjamin we included in the exhibition: “The illiterate of the future, it has been said, will not be the man who cannot read the alphabet, but the one who cannot take a photograph. But must we not also count as illiterate the photographer who cannot read his own pictures? Will not the caption become the most important component of the shot?” In this quote from the end of A Short History of Photography (1931), Benjamin highlights the image-text relationship, emphasizing the importance of description (which can be caption, date, and nowadays code). In the exhibition, we are trying to establish different typologies of material, but also to have a kind of equivalence between text and images–thus the quotes that are exposed as images.

The advertisement image plays a great role in this exhibition. Advertising is in itself a speculative form: it wants to make the product desirable for a potential consumer. It’s at the same time an image and the virtual promise of a transaction. And when they are confronted, the operational quality of the advertisement image becomes even more visible. Is advertisement the very form of image as currency?

Advertising has several purposes in this exhibition. The first is that it gives you a vision, an imaginary of something that is an ideal form. At the same time, it reflects society. It cannot be too abstract, because otherwise people would not be attracted to it, would not desire it. So, it’s a very interesting form of communication, and also reflection. It also has its specific aesthetics, and a very persuasive rhetoric (such as Kodak ad for the Recordak Miracode System, 1966: “If you don’t have a photographic memory, get one”)… It is very often extremely intelligent.

The other reason for our use of advertising in this exhibition is because it’s very often difficult to work on this type of technology: companies are very secretive about them, and you can’t go to their laboratories and ask them what they are doing. Sometimes, it’s the only material we can have. For instance, with Google, we made a lot of interviews, and everything was set for us to use it, but in the end the communication department stopped everything. They don’t want any information to filter out. That’s the principal reason why we must use the material from advertisements. To us, ads were a sort of found footage, where companies present themselves for selling what they are doing. And it already conveys a lot of information. I’m a fan of open access, and so far, we didn’t have any problem with what we used. We also used material scrapped for YouTube, and since we are an exhibition framed as academic research, we can use the material under the right of quotation for academic purpose.

One moment in the exhibition draws a very suggestive parallel between a 1971 ad from IBM and a very recent Alphabet ad.

Sometimes it’s easier to come with connection than explanation, they are more poetic. Our intention was to highlight the long existing presence of the computer in the field of visual documentation. This montage documents the historic link existing between computer companies such as IBM, and photography companies like Eastman Kodak. In the history of microfilm, dating from the 1950s, it becomes quite obvious that there is a predigital idea of exploring the depth of information gathered visually.

The first ad is an ode to modernity, claiming that you should embrace new technology because it is new, while the second, with its mixed media composition (16 mm, Polaroid, digital camera, smartphone, etc.), has a more nostalgic flavor, similar to the Kodak Carousel Don Draper advertised in a famous scene from TV-series Mad Men (s01e13, 2017). Is it one the major changes between the 1970s and now?

They aren’t so easy to compare, since the first is about information processes, and the condensation of data in microforms, while the second is about private use. But you’re right to say that there’s a shift. The interest of the ad from Alphabet is that it shows that every time we take a picture with our smartphone, we’re also giving away a clue from our behavior. This use of photographs is the beginning of a process which sees company coming inside the mind of the consumer and gathering qualitative information. The idea of the first ad was that all information that can be gathered should be used, while the second is a more indirect way to get inside people’s head. It’s a shift toward qualitative semantics.

Indeed, the first moment could be described as when capitalism finds the way to value the data, and the second is about the moment it must expand to private memory. This brings us to another quote shown in the exhibition, from « La conquête de l’ubiquité » (1928) by Paul Valéry. In the quote exposed, the poet imagines a future now realized, the technical distribution of art at home. The following of this text isn’t part of the exhibition but is rather interesting nonetheless: Valéry evokes the possibility of the creation of a “company for the distribution of Sensible Reality” (« société pour la distribution de la Réalité Sensible »), implying the possibility of a capitalist organization of access to sense data. Furthermore, the text ends by praising the advantages of home distribution of art for facilitating “the highest aesthetical productivity possible” (« rendement esthétique le plus haut »). What effect does digital capitalism have on artistic experience?

What we can derive from Valéry and this text that hasn’t circulated enough (it is at the core of Benjamin’s The Work of Art at the Age of Technical Reproducibility which quoted it in the Prelude of the 1935-first edition) is the idea that media creates our perception of reality, and that perception is shifting through reproduction of art. Media changes how we perceive, and how we engage with the world. In a way, you can consider it as empowerment: to choose when to experiment is a way to empower our senses. In the quote given in the exhibition, Valéry describes the shift toward the interior allowed by technical media, which is a very important discovery for modernity. But at the time, the interior was a place you could control. It is much different nowadays that there is not such thing as an interior. This brings us back to the Google advertisement getting into the brain of people: now these boundaries between private and public, interior and exterior are blurred.

Exhibition and Value

How do you think Capital Image reflects on the idea of values of photographic images?

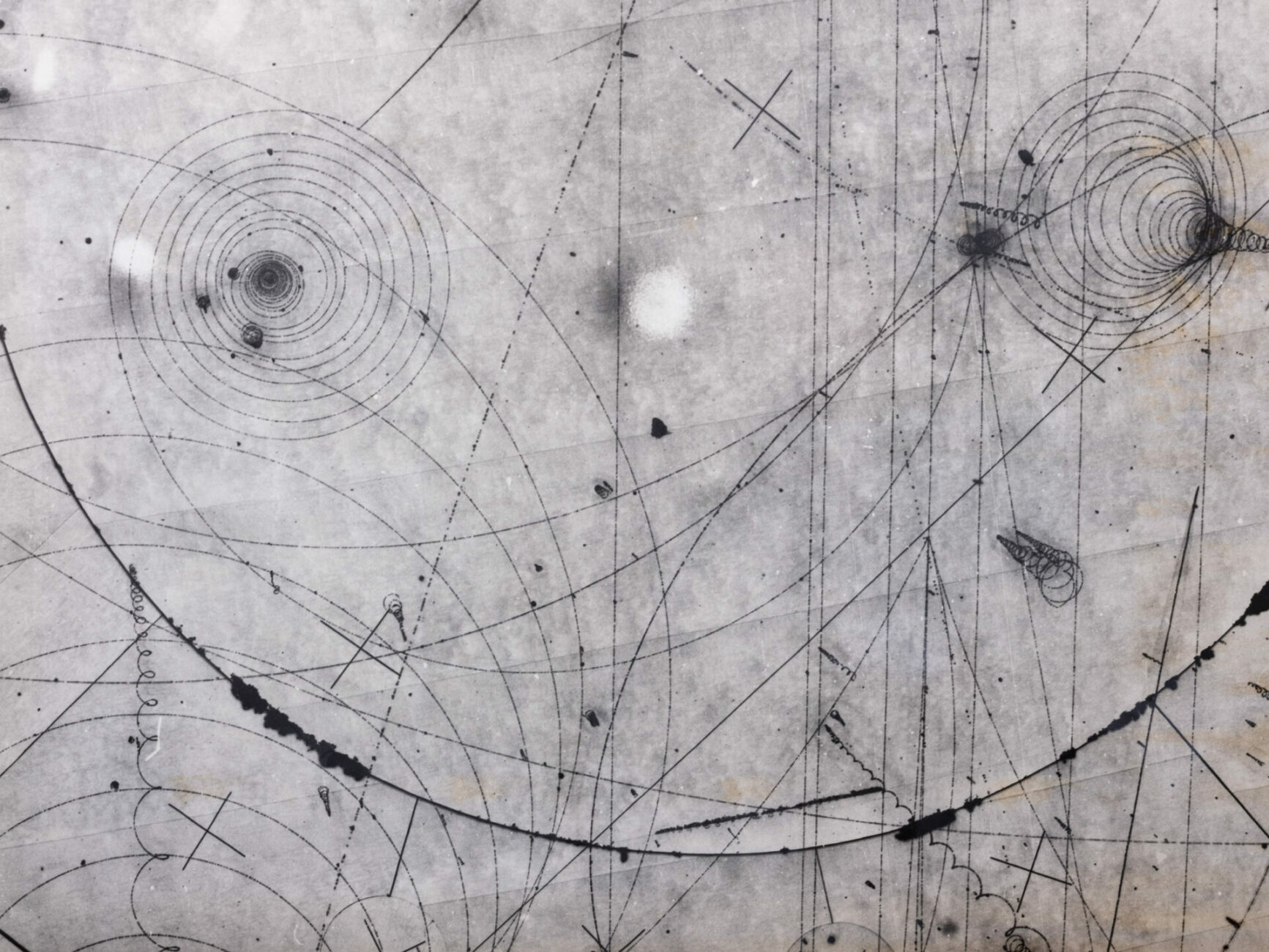

The architecture of this exhibition is informed by the first version we did a couple years ago, it was a test exhibition without any money. We asked the museum about the material they had in stock, and our idea was to recycle material instead of building it again and again. We used the boxes of vitrines, put off the glass and put the vitrine up. We used a very industrial way of printing, on a roll of paper with a standardized width, so you can see the materiality of the printing. The roll is bending a little bit, and is completely open, without any frame or glass. This was central to our conception of the exhibition and contradicting the traditional hierarchy of the display of photography. The art from Linke isn’t shown in a particular fashion, it’s hanging without glass; but we framed the images from CERN (which exist in 50,000 copies taken as raw material for analyzing the movements of atoms, looking like a Paul Klee, but having no values on the art market).

Image 9. Events of particle tracks in experiment LEBC, Lexan Bubble Chamber, CERN, Geneva, December 9, 1981.

Another picture in the exhibition is taken in the Eastman Kodak Archive in Rochester. It is an archive material from my research, in rather bad quality, but its exhibition in a different context and with a different strategy in mind (behind a glass from the vitrine) gives a certain value to it. It also comments on the idea of value in art photography. Value is always created artificially, because you can technically make a lot of prints, but the value is set by the art market. Most of the history of photography deals with reproduction with no “value”, such as amateur photography, images taken in the operational context such as the reconstruction of Notre-Dame.

Images 10 and 11. Reconstruction of Notre-Dame de Paris, Scanner 3D, Paris, France, 2023

Did the content of the exhibition change in this version shown in Paris? How does the reflection about the patrimonial value of Notre-Dame, its rebuilding financed by private funds and the massive use of 3D influenced your thoughts about conservation?

We got interested in that case via the public relation stunt done by Ubisoft at the time. We were in touch with the programmers of Assassin’s Creed: Unity who worked for two years on the 3D model of Notre-Dame made to include it on the game. That moment shed light on the question about who owns images, data, memory of cultural works, and in what way. It is a political and a cultural question. In the end, Ubisoft told us that the data wasn’t good enough to really help. But indeed, a department of digital technology was sent just after the fire: drones, photogrammetry, and complex dispositifs were in fact needed to access the place, that was condemned because of lead pollution. Then, they used technologies for the scanning in 3D. So first, the need for remote imaging technologies; then a lot of experiments. As it is always the case, war and disasters always help to push technology.

In fact, we saw the result made by a company sponsored by Dassault, which was the first time I experienced a convincing 3D environment. You put the viewing device, and with gloves you are able to turn around objects. This technology is used to make like a puzzle of the elements, and to give the ability to get it back together. This experiment of manipulating an object without touching it, the sense of view is trying to compensate the nonexistence of the object, was convincing. It shows that there is a value in these highly detailed reproductions. To me, there’s a direct link to Girard’s heliogravures. If you look at it in a close-up, it’s marvelous how much details it has. Like an object coming out of the paper. See the bulbs, which have a 3D effect, or the roots. There is an important source of information in 3D. We always thought of the history of photography as flat, 2D, but there’s also a strong history of spatial rendering in photography in the 19th century.

We noted this ambivalent discourse on the values of photographs in the exhibition. It is both a financial asset (copyable, exchangeable, spreadable) and a remain to be saved (in secret servers or special chambers, even inside vaults). It seems that there is an unresolved tension between photography as a key to exchange value and as an archive with a kind of aura to be saved (be it at a high cost of energy or space).

Take this photograph taken in the Iron Mountain Preservation Facility I visited for my first research. When I came back with Armin for the field work of this exhibition, after three days in the archive, sub-zero, with analog negatives and acetate, nitrate, polyester prints, the archivist from Getty Images told us that they wanted to give us a special treat, and show us the bit of pieces of the broken glass protecting the famous photograph credited to Charles C. Ebbets, Lunch Atop a Skyscraper (1932).

Why would you keep these? You cannot reproduce it, it’s broken. The point is that the value of the image lies not in the image itself, but in the copyright, because you can always come back to the material and prove the ownership of the image. It can seem paradoxical in this environment of endless digital copying, but every time this image is reproduced (on a postcard, for instance) they benefit from it. On the contrary, for companies such as OpenAI, there is no interest in procedure concerning copyright. Ownership must be vague to allow for the largest training dataset possible. This is the most prominent shift in value in contemporary imagery, and maybe we should rewrite the history of photography through copyright.

Interview held in English at Centre Pompidou, February 8, 2024.

Estelle Blaschke

Estelle Blaschke is a historian of photography. Her approaches place her work at the intersection between art and media history, and the history of science and culture, as demonstrated by the book based on her doctoral thesis, Banking on Images: The Bettmann Archive and Corbis. From 2015 to 2020, she led a research project on the history of microfilm at the University of Lausanne, and since 2020 has taught at the University of Basel and the ECAL. She is also a member of the editorial board of the journal Transbordeur. Photographie, Histoire, Société, as well as the projects The Migrant Image Research Group, Double Bound Economies and the exhibition Capital Image, which she curates with Armin Linke.