Noah Teichner

Comedy Objects #1: Slapstick Speculation

Abstract

Through examples of films, novelty songs, and comic monologues from the 1929 Wall Street Crash, this videographic essay and publication explore how comedy and the stock market were invested in a shared culture of liveness across media during Hollywood’s transition to sound. This is the first installment of Comedy Objects, a project that brings together archival research with speculative fiction to think about comedy workers in the United States during the Great Depression.

Keywords

slapstick comedy, vaudeville, media archaeology, stock ticker

Electronic reference to cite this article

Noah Teichner, « Comedy Objects #1: Slapstick Speculation (English version) », Images secondes [Online], 04 | 2024. URL : http://imagessecondes.fr/index.php/2024/12/comedy-objects-1-slapstick-speculation-english-version/

Statement by the Comedy Workers Group (1931)

Comedy workers in the United States are currently faced with a three-fold transition: in industry, in technology, and in form. In industry, the Keith-Albee and Orpheum vaudeville circuits, after having lost many of their performers to movie house presentation acts, were absorbed into the new film studio and theatre chain RKO (Radio-Keith-Orpheum). In technology, after a first period in which it seemed like synchronized sound shorts—dominated by Warner Bros.’ Vitaphone model of “canned” vaudeville acts—could co-exist alongside the silent feature, the entire industry has progressively gone “all-talking.” In form, vaudeville and film comedy have entered into a new chapter in their long-running dialogue, thanks to the possibilities of sound and language in slapstick comedy. Radio, another new medium of comic labor and performance, further complexifies this period of industrial, technological, and formal transition1.

In the current depression, it is essential to formulate a critical perspective on these changes that speaks from our position as comedy workers and as artists. It is for that reason that we have created the Comedy Workers Group and are developing the method of slapstick speculation.

Slapstick speculation uses the tools of comedy to think about comedy. It can be carried out on stage, film, record, or radio. In the “analytical routine” for one performer that follows, destined for the variety stage, we test this method on a first case study: the 1929 Wall Street Crash. Slapstick teaches us that “what goes up, must come down,” be it bodies or values. The “New Era” of endless prosperity hailed by pundits and politicians in the years leading up to the Crash was a set-up waiting for a punchline. Like (historical) narratives, gags depend on a play of expectations that lead to a comic climax. The Roaring Twenties have made way for a Great Depression.

In our routine, on a stage equipped with a stock ticker, telephone, radio, phonograph, and film projector, a monologist demonstrates how the “comedy objects” produced just before and after the Crash bring out the gag-like nature of this cataclysm. These films, records, and joke books also help to come to terms with the ways in which comedy and the stock market participate in a shared culture of liveness across media—a culture that includes not only vaudeville, radio, and sound film, but also the stock ticker.

Slapstick speculation invests in the futures of comedy by analyzing its present. It takes on the potential for comedy objects to object. Rather than rule out objecting from within the limitations of a capitalist mode of production, we seek out the sometimes all too brief speculations carried out by performers, gagpeople, stagehands, and technicians—by our fellow comedy workers, in short. And as comedy workers, we then produce new objects that speculate through the means of slapstick.

There is little chance that Slapstick Speculation will find its place on commercial vaudeville or movie house stage programs. Bookers’ narrow-mindedness and the stale mantra of “what the audience wants” prevents them from showing off analysis as entertainment. We would also receive letters from the lawyers of Mack Sennett Productions, Victor records, and others, threatening to sue us for non-authorized reproduction of their products. While we do not object to attempts at staging this routine—a first in a series of “comedy objects” for stage, film, phonograph, and radio—we accept its currently hypothetical state as a videographic essay. Let it be speculation on a future in which comedy workers have fuller control of their means of production, distribution, and exhibition.

Comedy Objects

Comedy Objects mixes archival research with speculative fiction to think about comedy workers during the Great Depression. In this project, I investigate comedy’s historical conditions of production and its possible forms of collective organization. While the Comedy Workers Group at the project’s core never existed, its members concern themselves with political and artistic issues that are based on first-hand sources. This informal collective of comedians, gagpeople, and technicians from the film and media industries of the 1930s takes on the crisis of the Great Depression in their interconnected fields of work. They create stage routines, films, records, and radio programs that explore the ways in which comedy objects can object.

Comedy Objects imagines the traces of the Comedy Workers Group’s productions and invents discussions between its members by means of lecture-performances, moving image installations, videographic essays, and publications. After a series of such installments, I plan to conclude the project with a feature-length essay film. All while excavating comic labor, working conditions, and political debates from the 1930s, Comedy Objects organizes anachronistic encounters between the materials of the past and their restaging in the present. The Comedy Workers Group speaks with a historical voice that remains in dialogue with today’s scholarship, media, and activism.

The Stock Ticker as Medium

In their 1931 videographic essay Slapstick Speculation, the Comedy Workers Group argues that the stock ticker can be conceptualized as a medium; not only as a communications medium, but as an entertainment medium that engages with the user’s senses in a specific way. The stock ticker produces a historically situated user experience that involves touch (the feel of the ticker tape between your fingers), sound (the eponymous tick that gives the device its name), sight (the horizontal flow of signs inked onto a paper strip), visuality (the mind’s eye theatre of transactions on the stock exchange floor), and a form of temporality dependent on synchronization, on liveness.

Not only can the stock ticker be theorized of as a medium, it is also a medium represented in other media; a medium remediated. In his study of Gilded Age financial capitalism, Peter Knight shows how the novels and short stories of the late 19th century were already translating the user experience of the stock ticker to produce dramatic effects that disseminated imaginaries of speculation2. It should come as no surprise that the visual and sonic attraction of reading the ticker tape would also draw the attention of the movies. The Mack Sennett talking short central to Slapstick Speculation’s arguments, Bulls and Bears (1930), is but one among many on-screen remediations of the stock ticker in early, silent, and sound film3.

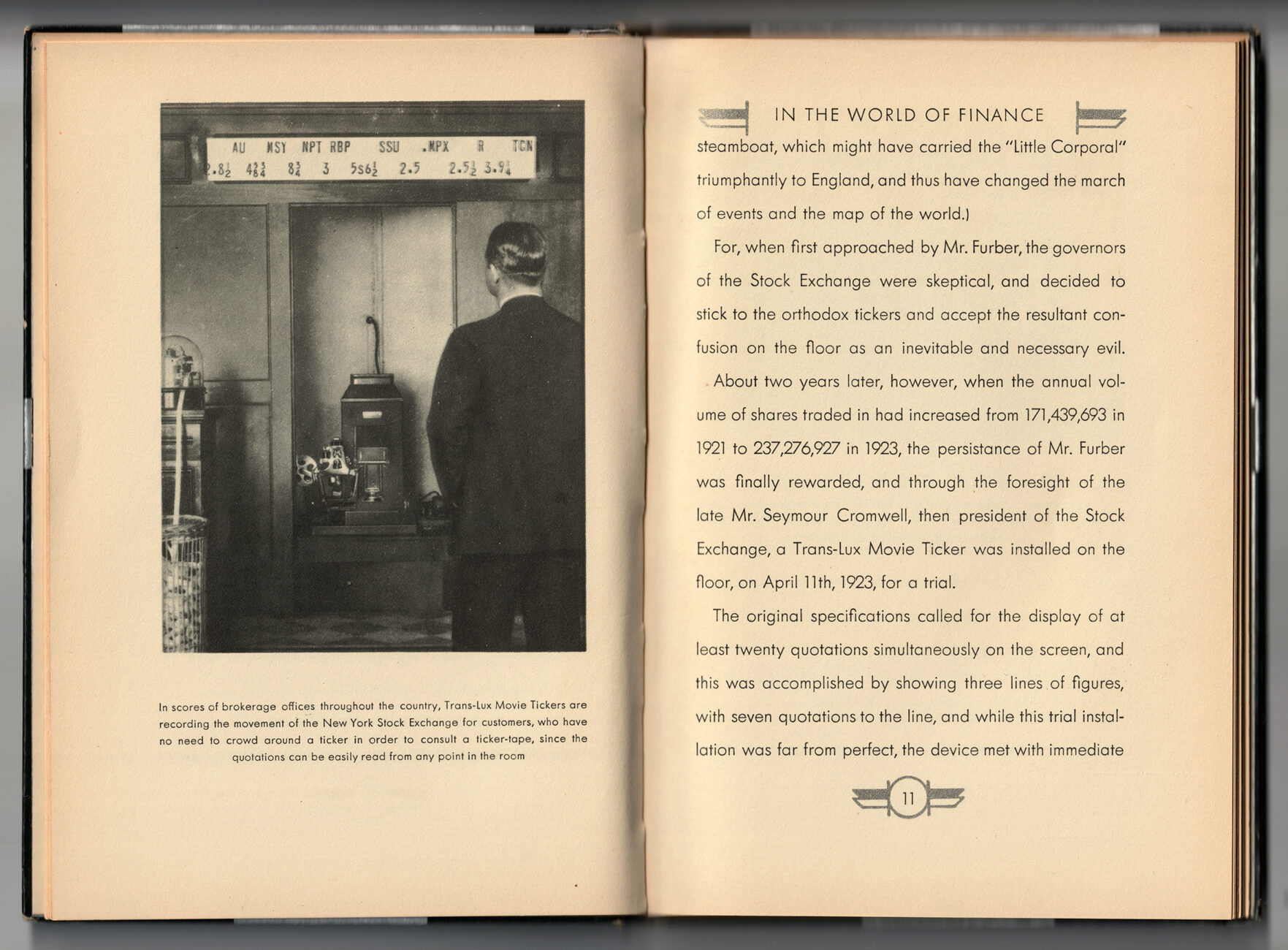

The connections between the ticker tape and the moving image screen went both ways. In 1923, the Trans-Lux Movie Ticker [Fig. 1] began to be introduced on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange and in brokerage firms. Instead of printing stock prices on a paper strip, this device projected the ticker’s characteristic flow of numbers onto a horizontal strip of a screen. The Trans-Lux Movie Ticker suggests that the medium of the stock ticker was not just represented in cinema; it’s user experience was also informed by moviegoing. Like all media, the stock ticker was inherently intermedial—its functions were defined and gained meaning from within a broader network of practices. Users of the stock ticker were also users of other media. Be it in literature, on the movie screen, or in radio, the ticker’s representations influenced its user experience, and vice-versa. Use and representation flowed together to shape how the stock ticker stimulated the senses.

“Live” and “Canned”

The stock ticker’s “live” temporality contributed to this user experience. Liveness is not an ontological condition; it is always already an effect4. The Comedy Workers Group draws on Philip Auslander’s theorization of this term in order to show how liveness-as-effect can be present in both “live” media (stage, radio) and “canned” media (film, phonograph). There is a multiplicity of possible intermedial relations between comic performances in which production and reception happen simultaneously (“live”), and those in which reception is deferred and repeatable (“canned”)5. Slapstick Speculation itself is very much a hybrid object: a “live” act “canned” by the typewritten text visible on screen. In this videographic essay, the group argues that the construction of liveness in the late 1920s not only involved film, stage, phonograph, and radio, but also the media infrastructure of financial capitalism.

The formulation of the stock ticker’s liveness dates from its early implementation. The adoption of the device in the 1870s had the effect of synchronizing markets across space and introducing continuous trading. Brokerage firms began to lease both stock tickers and private telegraph lines from Western Union in order to place orders in direct response to the quotations reeling out on the ticker tape6. This intermedial coupling of the ticker and the telegraph—like that of the ticker and the telephone in Bulls and Bears—reinforced the liveness of both devices; it generated a feedback loop that worked to construe the market as “live.”

Inevitably, liveness-as-effect depends on concrete material conditions. The stock ticker could not always keep up with the speed of transactions. On the heaviest days of trading during the Wall Street panic, the ticker fell hours behind in reporting sales from the floor of the New York Stock Exchange. In October 1929, liveness failed7. But the liveness of “canned” media like film and the phonograph took up the slack. The short and feature films, novelty songs, and comic monologues analyzed in Slapstick Speculation—the “comedy objects” of the 1929 Wall St. Crash—produced an effect of liveness through their intermedial relation to the stock market.

Daphne Pollard’s eccentric dance routine to the beat of the ticker in Bulls and Bears is just one example of synchronization during the early sound era. In the film’s final moments, the fallen speculator played by Bud Jamison quips, “Oh, I’ll be back in the market soon!” As this punchline suggests, gag cycles are like market cycles; their ups-and-downs link bodies and machines in an intermedial knot of performance. Made at a time when Hollywood tightened its sync with financial capitalism, Slapstick Speculation is a first attempt by the Comedy Workers Group at introducing interference into the circuit8.

Noah Teichner

Noah Teichner is a filmmaker, artist, and researcher. In his films, installations, and performances, he often reworks collected and archival materials to engage with the writing of history across old and new media. As a film and media scholar, his fields of research include comedy and popular entertainment, film technology, sound studies, and media archaeology. He is Assistant Professor of Film Studies at the American University of Paris and an associate member of the research center Esthétique, Sciences et Technologies du Cinéma et de l’Audiovisuel (Université Paris 8).

- There is also an ongoing shift in slapstick’s position within the cultural hierarchies of our field, in which so-called “low” comic forms are losing clout to “sophistication.” Such bids for respectability can be seen in one of the works analyzed in Slapstick Speculation, the Mack Sennett two-reel talking short Bulls & Bears (1930). The early-21st century film historian Rob King will provide a useful analysis of this shift in Hokum! The Early Sound Slapstick Short and Depression-Era Mass Culture (Oakland: University of California Press, 2017).

- Peter Knight, Reading the Market: Genres of Financial Capitalism in Gilded Age America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2017), 59-100.

- Bulls and Bears was scripted little more than a month after the October 1929 Crash and was already being shot by mid-December. Following January 1930 reshoots, it was released in March 1930. For details on Bulls and Bears’ production, see Mack Sennett Collection, Folder 69, “Bulls and Bears.” Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences; as well as Brent E. Walker, Mack Sennett’s Fun Factory (Jefferson: McFarland, 2010), 189-91.

- Philip Auslander, Liveness: Performance in a Mediatized Culture, 2nd ed. (London: Routledge, 2008).

- Some of the historical and theoretical concerns of Comedy Objects grow out of my doctoral research on phonograph records and early sound shorts dubbed “canned” vaudeville. In the first part of my dissertation, I attempted to show how long before the term “live” acquired its current connotation, “canned” was proffered by journalists and critics to comment upon recorded performances and their relation to what we would now call liveness. See Noah Teichner, “‘Canned’ Vaudeville and ‘Canned’ Media in the United States, from the Phonograph to Sound Film: A Media Archaeology of the Sound-on-Disc Vitaphone Shorts (1926-1930) [original title: “Le ‘canned’ vaudeville et la mise en conserve médiatique aux États-Unis, du phonographe au film sonore : étude média-archéologique des courts métrages Vitaphone au format son-sur-disque (1926-1930)], PhD dissertation, University of Paris 8, 2021.

- David Hochfelder, The Telegraph in America, 1832-1920 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 116, 102.

- See the photograph of the late stock ticker taken on October 29, 1929, reproduced in Maury Klein, Rainbow’s End: The Crash of 1929 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 234. Klein’s study contains a number of other examples of the ticker being saturated by transactions in the late 1920s. In 1930, Western Union introduced a high-speed stock ticker to help prop up the market’s liveness. “High-Speed Tickers to Serve Brokers,” Scientific American, March 1930, 199.

- Both Warner Bros. and Fox relied heavily on Wall Street financiers and investment banking in developing synchronized sound technology in the 1920s and in their successful campaigns to join the ranks of the majors in the nascent studio system. See Douglas Gomery, The Coming of Sound: A History (New York: Routledge, 2005), 35-6, 49.